Parenting as Redemption Arc

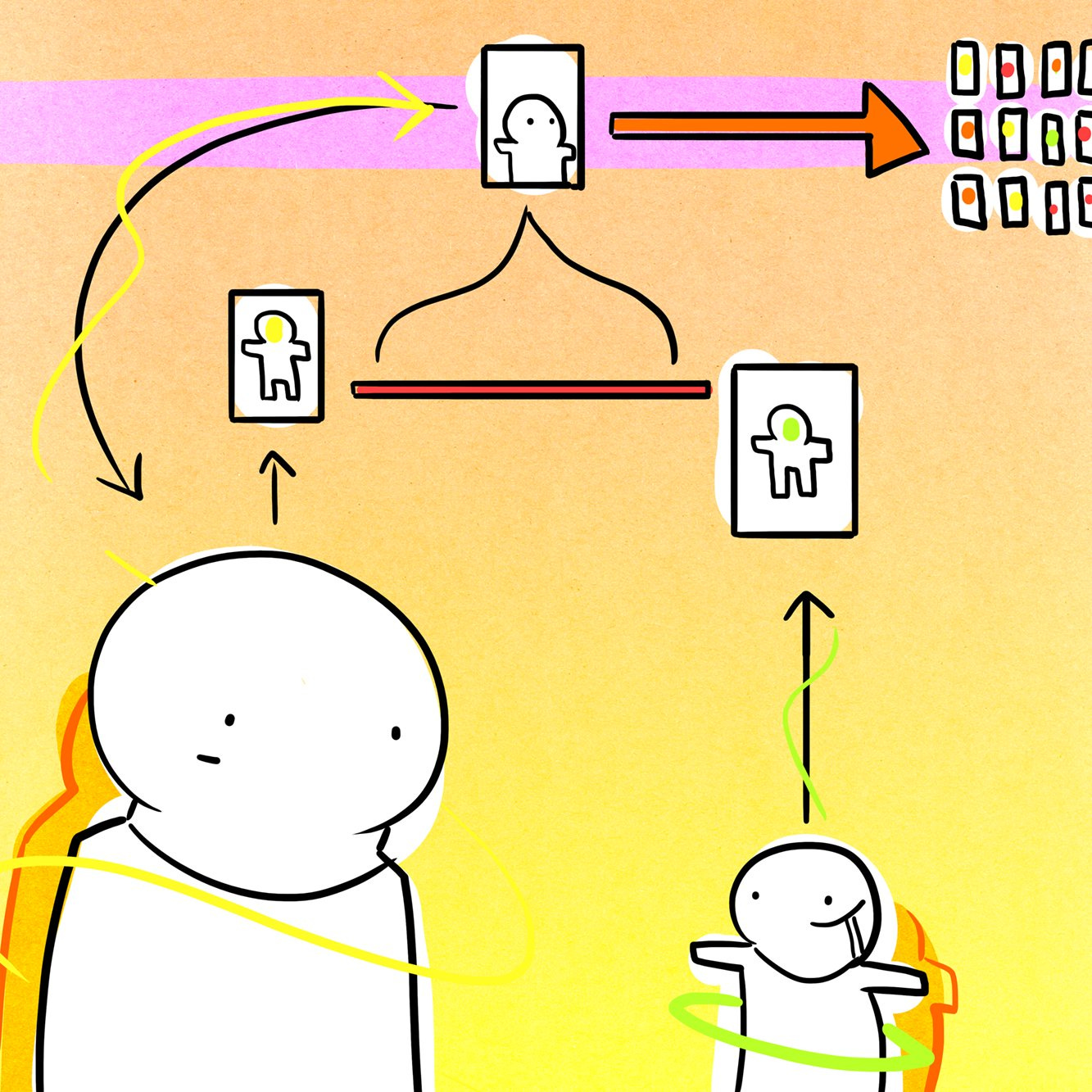

The self, served via homunculus.

A question I've often been asked over the last two years is: what's the most surprising part of having a kid? Normally my answer has been something about the parent-child bond.

Now, my answer is very different.

One of my favorite shows is ‘King of the Hill’.

One distinction I'd make between something like ‘King of the Hill’ and ‘The Simpsons’ is that, eventually, I started to identify with Hank (the father). I never "became" Homer while watching ‘The Simpsons’. I became an adult, and a dad, but it just never happened.

In contrast: eventually, as I got older, I started to see the plots and episodes from Hank's perspective rather than the kids. It just made sense. We're not similar as characters, but that switch happened. I wasn't "the kids" anymore. I was seeing the adults as the equals.

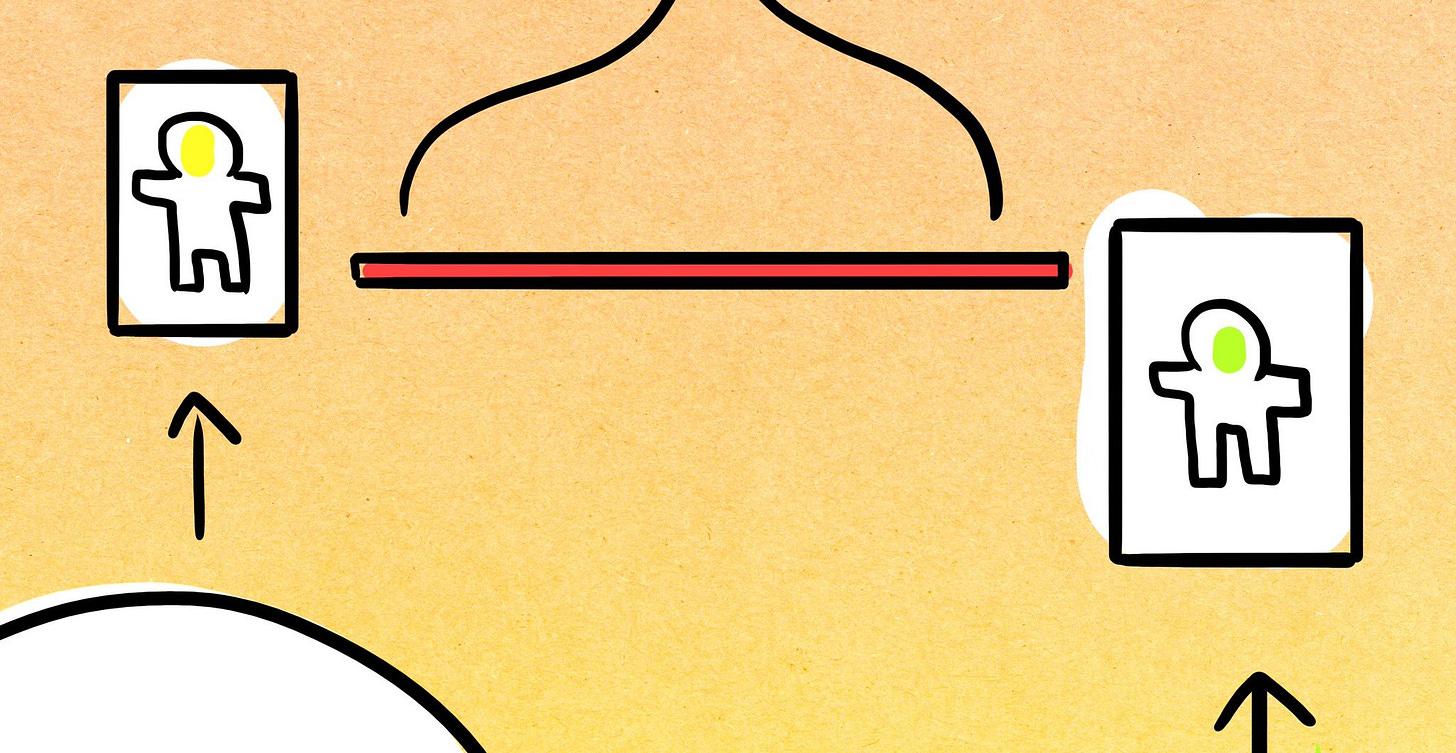

Well, if the adults are your equals, that means you're seeing the kids as kids. You're seeing their limitations and limited perspective as one of their main character features. Those things define what kids are, really - and most importantly, they're not totally aware of them.

By definition, a kid sees things from a kid's perspective. They literally have to - and that limitation is self-recursive. It’s total. They cannot know what it means entirely, even if they’re aware of it. That's "the whole game". It’s a closed limit.

The most unexpected part of having a kid has been experiencing that flip in my own life story, with my own childhood.

Having a kid means a few things: first up, you're literally looking at the kid a lot. It kind of looks like you - and you're going through all these childhood processes with it, while also planning and reflecting on your relationship.

What I did not expect, and what totally blindsided me, was the implications of this. Here’s a tangible one that i think will resonate with some people:

You're here, so you probably have weird interests.

For your whole early life, it’s quite possible that no one ever really asked you about these weird interests - and you were a kid, so you thought, “well… yeah, this makes sense”. I’m into something atypical, other people aren’t, so they dont ask me about it.

That makes sense - to a kid.

But when you have a kid, you realize that whatever this kid was into, you would obviously ask him about it.

In fact, I'd be into it because he's my kid. I would be genuinely curious because i care about him.

If my kid got really into accounting, I would find accounting interesting.

If he was reading books about accounting a lot, and watching videos about accounting, and wearing "accountant" t-shirts, obviously I’d ask him about it. I’d probably take him to accounting… things. Something like that would be front and center in my mind.

So, obvious question: why didn’t the adults in your life, when you were a kid, feel that way about you?

I mean, in this theoretical example, no one asked you about any of that stuff. Why not?

It’s uncomfortable answering a question like that. There’s really only a few places to land, and none of them are great.

If that example doesn't resonate with you, there’s a thousand others. You remember some time when you were a kid and something happened - you remember how the adults around you acted.

But now you’re the adult - and you would never act that way. So, why did they?

The first two years of parenting were just that process on repeat. I’d remember something from when I was a kid, and my perspective on it is totally flipped. Not trivial things - almost completely rewriting my life story.

I did not seek this out. It just happens. Frankly I would have preferred to not do that - I’m not exactly swimming in free reflective time here.

I never believed in… any psychology stuff, but now I do think there’s something to the framework of: you inherent this meta-narrative from your childhood, and then carry it into adulthood. It frames most of your life, usually without you realizing it (now paging the: post-structuralist psychology department, please report to the front desk).

But there’s something positive: a twist.

Everyone has unideal stuff from their childhood - and, for better or for worse, this is an axiomatic pillar of our culture now.

I’m slowly coming to the conclusion that, even absent any self-awareness about it: having a kid is the redemption arc from your own childhood.

Let’s take another random example: divorce. You're a kid, and your parents get divorced - or something else: they did drugs a lot. It could be anything.

So, what do you do with that? It’s hard to come up with a great answer here. You get over it, I guess. Alright. That’s… something.

But there’s really no flash or narrative there. Okay: you get over it. That’s not really a redemption arc.

One solid answer for what a real redemption arc could look like is: you have your own kid. You create a new smaller version of yourself, and then you don't do that to them.

I’m sure that’s not the only answer, but, it’s at least a pretty good answer. You (literally) see this new smaller version of yourself, and you get the satisfaction of seeing them get to go through life not getting bitten by the same animal you did.

And, it’s real. It really happens. It isn’t just a story you’re telling yourself.

This brings an interesting spin to the popular topic of people not having kids. If we carve out an exception for something like a religious celibate life, it’s hard to imagine some of my close friends really getting the full redemption arc from their childhood without this.

So, that's my real answer. What's the most unexpected part of having a child? That you go through your own childhood story over again - but this time, you’re an adult. You just keep turning over these stones in your past and reframing what’s underneath them. You’re forced to rewrite your own life story, piece by piece.

That wasn’t in any of the parenting books we read.

Putting the pieces together of ways your parents were able to do better than their parents is another interesting element to this. My dad for example said his mom didn’t consider it a successful whooping until he was sobbing and begging her to stop—it was essential for her to break his will—and she did this more days than not. Now, the scars of this explain so many things about my dad that hindered him throughout life—and as a consequence affected me—but he never beat the dogshit out of me to break my will like that.

Baby steps add up.

I had great parents but still understood places where they screwed up. Now I have the opportunity to fix those mistakes while screwing up in new, unique ways.